Translated into English by Aimee Van Vliet

Rest in Fornelli

The XXXIII Bersaglieri Battalion was not the only Italian unit to join the First Motorised Grouping on the front line at Cassino in February 1944. They were joined by the 1st Battalion “Arditi”, the 68th Infantry Regiment, the 51st Engineers Company and the Piedmont Alpine Battalion. Although General Utili would have preferred to have had a mobile unit with which to pursue the Germans, the 71st Motorcycle Battalion was conspicuous by its absence. It only arrived from Sardinia in July of that year. During that time, the number of men available to the Italian contingent grew considerably: from the 5.000 originally under General Dapino’s orders, their ranks swelled to 14.000. A significant force, which would grow further.

My grandpa and the other Bersaglieri, who had had their mettle tested in Sardinia, were not yet in decent enough shape to go into combat. They were stationed in Fornelli, a small town squeezed between thick medieval walls, immediately behind the front. It was there on the 21st March that my grandpa celebrated his 23rd birthday. There the men could get clean, eat and relax for another month before going back into active service. From their temporary quarters, they watched the clashes of the second battle of Cassino raging in tense silence, which began just as they arrived. While the crackle of gunfire from the front echoed through the surrounding countryside and the booms of artillery shelling shook and lit up the night sky, the inevitability of the ordeal awaiting them appeared before them in all its blind violence. The Italian front was nothing like what they had experienced in Corsica. Seen from their vantage point, the Gustav line seemed like a hole of mud and iron, capable of swallowing thousands of men a day in a blind, unstoppable fury. The idea of setting foot in that hellscape extinguished the Bersaglieri’s smiles and threw them into an unnerving wait, of prayers whispered at night and cigarettes smoked with trembling hands. During that time my grandpa tried, as much as possible, to move among his men calmly and confidently, to instill in them the courage that he himself could barely muster.

On the day they arrived in Fornelli, Montecassino Abbey was razed to the ground by allied bombers. It was a bright winter morning, with crisp, clear air that tingled on the face and dazzled the eyes. The Bersaglieri had barely stepped off their trucks when they saw the sky fill with American aircraft. They appeared to be almost floating above the jagged silhouette of the Apennines, as if suddenly hesitating. But a second later the clear morning air was ripped apart by what felt like a single, dark roar, and the abbey disappeared under the weight of over 350 tons of high explosive and incendiary bombs. The event shocked everyone that witnessed it: a German lieutenant said that it seemed as if ‘the mountain had disintegrated, shaken by a giant hand’, while General Clark wrote that ‘that morning… the thundering salves of explosions seemed to split the mountain in two’. Fortunately, the Germans had sent all the artworks that were ordinarily held in Montecassino to Rome for safekeeping towards the end of 1943, in a project backed by Abbot Gregorio Diamare and designed by Captain Maximilian Becker and Lieutenant Colonel Julius Schlegel.

That February, the Italian soldiers found themselves involved in an incident that risked jeopardising relations with the French contingent that was providing support in that section of the front. An episode which, given what happened after the Gustav line collapsed, seemed like a sinister premonition.

In the town of Colli a Volturno, close to Utili’s headquarters, an Italian soldier had killed a French goumier who had attempted to rape a local girl and, having not succeeded, was walking off with her family’s donkey. The girl had raised the alarm, and the Italian soldier, intercepting the miscreant and realising that he was prepared to defend himself with his weapon, shot him point blank.

Lieutenant Colonel Lombardi, Chief of Staff of the Italian Grouping, rushed to General Guillaume, commander of the French colonial troops, to avoid a diplomatic incident. To his surprise, Guillaume welcomed him with total calm: to him, one Moroccan soldier more or less made no difference. This attitude speaks volumes about the esteem in which the French command held their colonial contingent. The Italian soldier at the centre of the incident was still put on trial by a French court, according to standard procedure, but he was acquitted with a verdict of self-defence and the compliments of the judge.

While my grandpa and the Bersaglieri were preparing to return to the frontline, the rest of the Italian contingent was busy reinforcing its positions, demining the area in view of future operations and remaining in contact with the Germans via intense patrol activities. Indeed, it was important to keep the enemy on its toes between battles, probing their defensive capabilities and gathering information on their positions. General Utili organised several patrol squads to goad the Germans day and night, in woods and on snowy slopes.

Even though these actions were small in scale, they still involved a degree of risk. Shootouts with German patrol or defensive units on the enemy line were frequent and unavoidable. The Grouping lost its first soldier in a skirmish of this type on the 18th February, followed by another on the 24th. On the 4th March one dead soldier, two injured and one missing in action were recorded, while a further seven went missing on the 15th of the same month. It was a steady trickle of fatalities.

The Germans don’t give up

On the 15th March the Allies launched their third offensive on the Gustav line. Having pushed back two German counteroffensives, New Zealander and Indian troops attacked Cassino and the monastery, after devastating artillery shelling had reduced the town to rubble, becoming an excellent series of defensive positions for German troops. The arduous battles, often fought man on man and from crater to crater, dragged on until the 24th March, when the Allies threw in the towel and abandoned the offensive due to their heavy losses. When the ceasefire order was given, the monastery was still in German hands, while Cassino had been only partially occupied by allied troops. The front, at that point, had become a dotted line running from one ruin to another.

At that time, advancing beyond the Gustav line became a serious problem for allied command, as nerves and irritation began to spread. Thousands of men had been thrown into the meatgrinder for several weeks, without managing to dent either the German defences nor their own desire to fight.

Not even the allied landings at Anzio on the 21st January, north of Cassino and thus behind the frontline, had succeeded in turning the tide. General John Lucas, commanding the operation, had moved with excessive caution, consolidating his positions before pressing inland. Kesselring therefore had time to move several units to the area of the landings and pen the Americans into the small bridgehead they had carved out for themselves on the coast. The allied positions were clearly visible to the German artillery, who therefore spent weeks pounding them, in an increasingly bloody siege. Lucas was heavily criticised by Churchill for his indecision, saying that he ‘had hoped to unleash a wildcat on the shore’, and instead ended up with ‘a beached whale’. One month later he was replaced by General Lucian Truscott.

Hitler had seen in the battles of Cassino and Anzio an excellent opportunity to inflict a searing defeat on the Allies, at a moment when the Red Army had launched its cavalry towards Germany, and the spectre of landings in France had begun to appear on the horizon. “If we can annihilate them there, there will be no more landings anywhere” he said to Walther Hewel, one of his few personal friends. And for a few weeks it seemed as though events supported that point of view.

Via Rasella

Another event contributing to this dramatic situation was the Ardeatine massacre, the Germans’ vicious retaliation for a partisan attack in Rome on the 23rd March in Via Rasella, coinciding with the end of the third battle of Cassino.

A Patriotic Action Group, a group of Communist partisans, had been tracking the movements of the 11th company of the third battalion of the Polizei Regiment Bozen, a military police force that crossed the city along the same route every day. The partisans had sent word of this possible target to their command, and Giorgio Amendola, the Communist member of the national partisans’ military council, had given authorisation to strike, specifying that the Bozen ‘were to be the target of an attack’ and even suggesting ‘the location for an explosion: Via Rasella’.

Furthermore, a previous partisan attack on a Roman fascist cortege, which killed 3 people on the 10th March, had provoked no German reprisals. British-American command, who were at that point in considerable difficulty on the Gustav line, had asked the partisans’ military council to attack Germans even inside Rome. The capital had in fact been declared an open city as early as August 1943 by Italian authorities, although the Germans continued to use it as a logistical base, ruling it with a heavy police presence and using the Casilina and the Tuscolana roads to reach the frontlines at Anzio and Cassino. There seemed no reason not to attack a target which, in circumstances, seemed useful and legitimate.

The partisans prepared an 18-kilogram TNT bomb and detonated it at 3:30pm, causing an explosion that ripped open the road, damaged several buildings and smashed windows throughout the surrounding area. Immediately after the explosions, the partisans threw hand grenades at German soldiers and raked the street with machine gun fire, with a final toll of 33 dead and 53 injured, as well as 2 Italian civilians who found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. When the attack occurred, Amendola was in a meeting with De Gasperi not far away. Hearing the explosions, Amendola said ‘That must be one of ours’. ‘Must be’, De Gasperi replied looking at him.

As soon as the Germans realised what had happened, they received a furious order from Hitler to raze an entire neighbourhood of Rome to the ground in retaliation. Kesselring and other officers intervened to avoid an action that they considered excessive, and agreed that it would be an acceptable ratio to kill ten Italians for every German killed. It should have been the Bozen Battalion’s dubious honour to carry out the vendetta, but, regardless of the circumstances, they declined. Clearly, barbarity remains a choice.

The task was thus handed to Herbert Kappler’s SS, who prepared a list of Italians to be executed at the Ardeatine caves, which were recesses in the rock face that opened onto Via Ardeatina. Several of the prisoners held the the Via Tasso and Regina Coeli prisons were on the list, including several Jews and members of the resistance, as well as citizens seized at random during raids in the city. When the reprisals began, Kappler himself joined in the shooting, encouraging his men and plying them with brandy. In total, 335 people were killed, five more than the ratio set out by German command would have required. Killing them all took almost five hours – from 3:30 PM to 8:15 PM of the 24th March. Once the operation was completed, the Germans blew up the entrances to the caves in which they had piled up the bodies, then left.

The Nazi reprisal took place exactly 24 hours after the attack. In this short space of time, no attempt was made to identify those responsible for the attack, nor any request that they turn themselves in to the German authorities was issued, as confirmed by Kesserling himself in 1946. Not only that, but the entire incident was covered up: German and Italian radio stations did not report on the attack, while a German press release confirming that the reprisals had been carried out was only issued after the fact, on the 25th March. Clearly, the priority was to get revenge on the Italians as quickly as possible, with no investigation, warning or communication.

The brutality and the scale of the Nazi’s vengeance were a body blow to the CNL (the partisans’ council), which held animated, tense discussions on the attack and its consequences, almost reaching a split over the question of its legitimacy and usefulness. A press release supporting the partisans was only issued halfway through April, although it was backdated to the 28th March to cover up their initial hesitation. The message, published in l’Unità, stated that ‘under the pretext of reprisals for an act of war by Italian patriots (…) the enemy massacred (…) men who were guilty of nothing more than loving their country (…). They were not executed but murdered.’ These views were reiterated during the post-war trials of Herbert Kappler in the depositions of Amendola and two other members of the CNL military council – Sandro Pertini, a future President of Italy, and activist Riccardo Bauer. All three confirmed that the attack had been ‘carried out by a military organisation’, in compliance with the ‘general orders’ of the council.

Regardless, the attack and its consequences were an indelible trauma that resounded through the ages, not only for the general population but also within the ranks of the partisans. Until then, the CNL had considered it opportune to strike the Germans anywhere and with any means, and that they did not need to sign off on the plans of individual action groups, for reasons of operational secrecy. The failed uprising in Rome as the Allies approached, an operation that the forces of the left wished to model on Naples the previous year, can be seen as a direct consequence of the arguments triggered by the events of Via Rasella, which saw the moderate wing of the CNL emerge with the upper hand.

Operation Diadem

In this tense climate of growing violence, the Allies began to reflect on how best to approach the Gustav line. Having lost three battles, there was a clear and urgent need to change tactic and unblock the stalemate. General Clark, commander of the American 5th Army, was particularly shaken by recent developments and in April he returned to the United States for almost two weeks of meetings on the future of the war, during which time he was given access to the plans to invade France. In the meantime, the Allies had understood that they needed a broad-based operation to breach the Gustav line, which would mobilise a broad section of the front, given that previous attacks focusing on specific sections had all inevitably failed.

It was thus that the plan known as Operation Diadem took shape. It had been designed by the Chief of Staff working for General Alexander, the commander of all allied forces in Italy. It was to be launched in May, when the drier climate and the higher temperatures would allow allied tanks ease of movement, as previously they had been hindered by mud.

In preparation for this operation, the Allies began to transfer part of the British and Canadian contingent posted on the Adriatic coast to Cassino, as reinforcements for the forthcoming attack. At the same time, they began to alternate periods of radio silence and periods of intense activity, to confuse the enemy about their intentions. Lastly, they mobilised the Italian contingent, which was to advance towards the Meta Mountains to reinforce the right flank of the allied position in front of Cassino, creating an unassailable linchpin that could be relied on for the final attack.

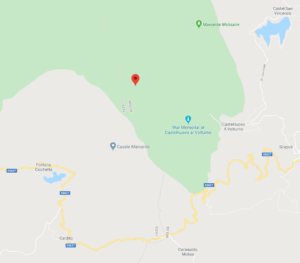

When the Allies contacted Utili to ask him to bring his men forward again, he didn’t need to be asked twice. The first target to be captured was clearly Monte Marrone, which loomed over the Italian section of the frontline, and which the Germans were using to dominate the valleys below it.

Before launching the action, though, the Grouping went from being under the orders of the French Army to the Polish. Without moving, the Italians had gone from being on the far-right hand side of the American 5th Army, which included the French, to being on the far-left hand side of the British 8th Army, which comprised the Polish.

The news of the handover spread on the 10th March, when General Anders, the commander of the Polish forces, visited Italian headquarters at Scapoli with an interpreter to meet with Utili. During the meeting he made an excellent impression on the Italian general; he appeared elegant and spoke passionately about Italy and its people, fighting for the liberation of their country.

The final transfer took place on the 26th March, after the end of the third battle of Cassino, when General Guillaume went to Scapoli to bid farewell. Clark, however, wrote to Utili to take his leave of the Italian contingent as follows: “The Grouping has made a material contribution to the success of our operations, while facing difficult terrain, inclement weather and a relentless enemy. I was delighted to have had it under the orders of the 5th Army.”

From that moment onwards, Polish troops soon began fraternising with the Italians, aided by the fact that they had never been in direct combat with them, unlike the French. Most Polish soldiers found it hard, however, to accept cooperation with Italian partisans, given that on the whole they were fiercely anti-Communist. Anders had indeed been injured and captured by the Soviets in September 1939 when they had divided Poland up with Hitler’s troops. Imprisoned at Lubjanka in Moscow, he had also been tortured, then released in July 1941 when the Nazis invaded Russia. Having formed an army made up primarily of former Soviet prisoners, he was then drafted into Allied formations and eventually sent to Italy via the Middle East. His men lost no opportunity, during the Italian campaign, to remove all symbols of Communist resistance they came across, which led to them receiving the nickname ‘Anders’ fascists’. In spite of their common goal, the relationship between them and the Italian partisans would always be strained.

Attack on Monte Marrone

By the end of March, everything was in place for the planned assault on Monte Marrone. The ground was covered in snow at the time, and before any operations could be launched, reconnaissance missions had to be carried out to gather information on the German forces in the area and the paths to be taken to reach the target quickly. The task was entrusted to the Piedmont Alpine Battalion, which included around sixty expert and specialist mountaineers, perfect for this type of challenge. In view of the mission, they were provided with American uniforms and high mountain equipment, which impressed the Italians by its sophistication.

The Alpine captain De Cobelli, along with two other explorers, set off for the south face of Monte Marrone at dusk, reaching the summit during the night before returning to headquarters still under the cover of darkness. Thanks to this sortie, Utili realised that the summit had not been permanently occupied by the Germans, who were moving around the area but only occasionally appeared there. It was decided then that sending troops in greater numbers to occupy the summit in one push was feasible. De Cobelli was later killed in March 1945 during a battle with the Germans, and he was awarded a gold medal for military valour for the following reason: “An officer of legendary valour, repeatedly decorated in previous campaigns (…). In a reconnaissance mission behind enemy lines, accomplished in order to assess the continuity of the enemy’s occupation, on a position that once captured would safeguard our defensive integrity and create the necessary conditions for future offensive actions, he fell a hero”.

In view of the operation, Italian artillery was positioned in Scapoli, to the right of the mountain, and in Cerasuolo, to the left, in order to encircle the Alpine troops with cover fire. The Cerasuolo battery was however quickly identified by the Germans and over the following days was subjected to constant counterbattery fire. Italian canon fire was adjusted to defend the summit from possible German counterattacks. Given the reduced space around the summit, caught between the rocky ravine on the Italian side and the thick woods on the German side, no more than 200 men could occupy it at any one time. Once they had captured the summit, which was around one kilometre long, the Alpine troops stationed there would have to defend it with nothing more than rocks, mines and a few rolls of barbed wire. The rest of the Piedmont Battalion occupied itself with resupplying the units to be positioned along the line, who had to travel light, carrying only the supplies needed for combat, their equipment consisting only of weapons, munitions and hand grenades.

Utili met with Polish command before sending his men into battle, receiving valid observations from General Sulik, the commander of the Polish 5th Kresowa Division. Sulik implored him to capture Monte Marrone as soon as possible, given that once the snow melted it was likely that the Germans would establish a more stable occupation there, that he should expect a German counterattack and that he should then continue to advance westwards towards Monte Mare, which if captured would prevent enemy observation of the sections of the front to the right of Cassino. Lastly, Sulik suggested attacking in the night of the 30th March, once Polish artillery had taken over from the French and would therefore be in a position to help the Italians attack, if necessary.

This was indeed what happened. On the 30th March, Utili set up an advance command post at the foot of Monte Marrone. At 3:30 in the morning of the 31st March, the order to advance was issued, and the Piedmont Alpine troops began marching towards their targets. The second company moved to the left, along a path covered with compact snow, which they climbed with the help of crampons, ending up on the lower peak of the ridge, at around 1600m altitude. The first and the third companies, on the other hand, took a steeper track to the right, climbing through ice and snow-covered gulleys, using rock climbing equipment. Having completed the ascent, they set up camp on the higher peak of the mountain ridge, at 1770m altitude. The Alpine troops had therefore managed to open a route up the toughest face of the mountain, in the dead of night, dragging with them not only ropes, crampons and pickaxes, but also their weapons. An achievement for the annals of mountaineering, especially considering that the route, following a few modifications and some maintenance work, is still accessible today.

So it was that at 7 AM on the 31st March, Monte Marrone was occupied without a shot being fired- the Germans hadn’t even noticed. Defensive activities began immediately, to install barbed wire, lay mines in the wooded area facing the line, set up the heavy machine guns and assemble an entire cannon that had been dismantled in the valley and carried up to the peak on the soldiers’ backs. They expected a German counterattack and they had to prepare quickly.

The first contact with the enemy took place on the 2nd April: a patrol of six German skiers coming from Monte Mare approached Monte Marrone but, having spotted the Italian positions, backed off to avoid a fight. The next day, shortly before 6 AM, and during the night of the 4th April, several German patrols came within range of the Italians to probe their defensive capacities and their reaction times. The Alpine troops opened fire every time, and the Germans disengaged, not before leaving at least 4 dead in the field.

Return to the frontline

As the Germans were intensifying their activity on the front, my grandpa’s unit at long last received the order to leave their safe haven in Fornelli and move to the frontline. The XXXIII Bersaglieri Battalion was positioned to the south west of the peak of Monte Marrone, quartered in mountain refuges in Casale Mainarde and Masseria Capaldi. Returning to action six months after their last battle in Bastia seemed surreal: once again, my grandpa and his men were called on to face their deepest fears and risk their lives. But, as facing a clear and present danger is something of a liberation compared to imagining it, the return to the frontline was greeted with no little relief. In any case, home lay beyond the Gustav line; it was better to get it over with and finish things, however they would end.

As soon as they arrived at the front, my grandpa and his men began to patrol their section of the line and reinforce it in case of possible attack by the Germans. It was precisely during one of their sorties on the steep, wooded slopes between Monte Marrone and Monte Mare that they had their first encounter with enemy fire on Italian soil.

One of the most disconcerting experiences that can arise in modern warfare must be to be targeted by bullets before you even hear the shots fired, if they come from far enough away. One afternoon, my grandpa was guiding a handful of his men on a patrol mission along the front when, from an unknown location, a German machine gun sighted them and opened fire. A fraction of a second before hearing the lengthy crackle of the weapon firing, similar to that of a zip being closed quickly, he had felt the rushing air from the bullets whistling past him, like a breeze wafting over his uniform.

In a split second he realised what was happening and he jumped forward, surging into a breathless sprint while enemy bullets raised clouds of dust from the earth around him.

“Get down!” he screamed, his voice exploding out of his stomach and splitting his throat with the force of a roar.

His men threw themselves to the ground on either side of the path they were following, while he continued to run, his legs lighter than he had ever felt them, his lungs empty as he forgot to breathe. His entire being had been compressed and distilled into the whirling steps that fell one after another in a line: he perceived nothing, he thought of nothing, time itself seemed to have stood still, suspended in an endless present moment between past and future.

Out of the corner of his eye, he eventually saw a bomb crater to his right, and without thinking he changed direction to reach it. The German machine gun fire, which until then had been following him, went beyond him when he dashed to one side to reach the hole. A moment later he was flying through the air into the ditch, his arms stretched out in front of him, diving headfirst with all the strength available to him.

I remember that when my grandpa told me this story, he told me with a smile that he had almost jumped past the crater. For a second he was afraid he wouldn’t make it, not because he didn’t have the energy, but because he had used too much. Controlling it, in that moment, was impossible.

He landed on the opposite wall of the crater, hitting it at full speed, chest first, with no chance of softening the impact of his fall. The collision made him bounce backwards, rolling like a rag doll to the bottom of the crater, where he found himself missing his helmet and tangled up in his gun’s strap. As soon as he could lift his face from the dirt, he found himself on his hands and knees, his hands gripping the earth while his stomach forced up everything he still had inside.

From a distance, Borghi’s muffled cries reached him as if in a dream. “Cover fire! Cover fire!”. Suddenly, the men who were with him reacted, and the air was filled with the deafening roar of Italian rifle fire, aiming at the German position that they had spotted in the meantime. Faced with the volume of fire, the enemy machine gun fire thinned and became less accurate, so that my grandpa could risk the move to put his helmet back on.

A short time later, he heard heavy footsteps running towards him. When he turned to look back, he saw Borghi’s dust covered face pop up above the crater. “Get out of there now, come on!” he was shouting, holding out his hand. Gritting his teeth, he jumped towards him, grabbed his arm and let himself be dragged out of the hole. He looked at Borghi for a second then lifted his rifle, joining his men to return fire on the Germans.

There was no way of aiming accurately from that distance, and it was pointless for all involved to start a long battle in those circumstances. The only option was to get out of there.

“Move now! Move! Get out!” my grandpa shouted while he reloaded. Still firing, and taking shelter where they could find it, he and the other soldiers retreated down the hill, moving as quickly as possible away from the spot where they had been ambushed. Once they were at a safe distance, they stopped to catch their breath and check that no one had been injured.

Luckily, they were all fine, and in a silence broken by occasional nervous laughter they sat down to smoke a cigarette in their sweat-soaked uniforms. “No more pranks like that, Sir” Borghi said to him, smiling. My grandpa looked at him as he inhaled the smoke, then rested a hand on his shoulder, staring for a couple of seconds. “Thanks” he answered. “Just doing my job” said Borghi, picking up his rifle. It was time to march on.

A short time later they arrived back at base camp, safe and sound, where they reported the possible German positions they had come across.

The accident

Luckily, I have never had to experience war as my grandpa did. But on one occasion I did find myself dodging death at his side.

It was a dark March night, I was thirteen years old and I was in the car with my family, coming home from a day trip to the nearby city of Ferrara, where we had gone to see an exhibition at Este Castle. My grandpa was driving, my sister sat next to him in the passenger seat. My grandma, my mother and I were sitting in the back, with me in the middle seat. My grandpa was driving slightly too fast on the state road, but no one took any notice – we were all chatting animatedly, and I remember that we were laughing about something funny that had happened to me at school.

Suddenly I saw the outline of a car looming in front of us, darker than the surrounding night, in the middle of the carriageway, where it shouldn’t have been. A failed attempt to overtake, or a miscalculation – I’ll never know. In a second, the headlights of my grandpa’s car lit it up and I instinctively grabbed the headrests of the front seats.

I remember the next few seconds as if they happened in a long dream, with a feeling of observing the scene from afar. It was an almost pleasurable sensation, taking my body far from the place it was trapped in, to a safe, protected place, where I could relax and enjoy the luxury of not having to worry about what would happen.

While my consciousness floated somewhere else in mid-air, I heard plate metal smashing, the sound bursting my ears. I found myself thinking, with detached curiosity, that the accident I was experiencing would be fairly serious. The collision at around 120 km an hour had flung our car over to the other side of the carriageway, like a billiard ball ricocheting off another. As we were moving, I saw the lights of a car travelling in the opposite direction moving quickly towards us.

I prepared myself for another head-on collision, while it dawned on me that I would probably die very soon. I remember thinking it with surprise, rather than with sadness or fear. Until that moment I had not considered that eventuality, and the fact that it came to me so soon in my life made me feel like I had been the victim of a bad joke. It would be a shame if it happened, I thought to myself. But while I tried to digest that thought another popped up in the margins of my consciousness. It had the consistency of a warm hand on my head, and it calmed me immediately. “You just need to be patient enough to wait for all this to be over” it said. I immediately decided that if holding on for a bit longer was all I was required to do, I could do it.

The final head-on collision had brought the wild trajectory of our car to a halt, with the result that I instantly felt myself being sucked back inside my body. The safe place I had been in for those few seconds, which to me had seemed so long, had disappeared, and the real world had taken form once again.

The car was a wreck: a mangled collection of sharp edges, where nothing was where it should be. My grandpa was groaning, collapsed on the steering wheel, and my grandma lay unconscious between the two front seats, having been thrown forwards towards the windshield. Her breathing was ragged and came out as a laboured gurgle. My mum and my sister were curled up in the shadows, where I couldn’t pick out any details.

Then I turned my gaze on myself and realised two things: the car was filling with smoke, and my left arm was covered with blood. I was suddenly afraid that the car would burst into flames, and in a moment I had kicked open the back door and jumped out, completely uninterested in my family. I would feel some shame for that reaction afterwards, but in that moment it was unavoidable.

Finding myself standing next to the car, I touched my arms and legs frantically, in an attempt to find out where I had been injured. I realised straight away, with no little relief, that the blood on me was not mine, and was probably my grandma’s. This was another feeling I would later question. There is a humiliating aspect to experiencing the full uncontrollability of the survival instinct.

As luck would have it, the accident had happened not far from a service station. As soon as I returned to something like reality, I ran to the petrol pump, aware that there I would find a fire extinguisher to use on the car and ward off the risk of fire. I found one lying around somewhere and I tried to lift it. To my surprise, I was unable to. I looked down at my hands and I finally noticed that I had two broken fingers, probably due to the fact that I had gripped so tightly to the front seats during the accident. I still couldn’t feel any pain, but lifting any weight was impossible. Luckily, one of the customers at the service station sensed what I was trying to do and took care of it for me.

Knowing that our car was safe gave me some relief, but it also allowed me to focus on another priority. On the other side of the road I saw the car that had caused the accident. The left-hand side of it seemed almost to have exploded in the collision, and the person driving it was still inside, conscious and apparently in good physical condition, but bleeding from their face. I strode over and realised it was a woman. I remember her black curly hair and the mantra that came from her mouth… “What happened? It wasn’t my fault… What happened?”.

When I reached her, a red mist fell over my eyes and the whole world fell away – there was only her face, as clear as if it were the light at the end of a tunnel. I started to insult her with every breath in my body and I flew at her car door, intent on pulling her out. I had no clear plan, but I remember very clearly that I wanted only to seek revenge, punish her. I’m not sure I would have managed it – I was still a young boy and had two broken fingers. But at that moment it didn’t matter – the rage I was hurling came in torrents and I feared no consequences.

Fortunately, someone noticed what was happening. I felt two strong arms grab me from behind and carry me away, far from that car. I tried to free myself, but I soon gave up. I turned and saw a man looking at me with concern. “I’m fine now, thanks” I said. He let me go and held my gaze for a moment longer. I remember his thick white moustache and his dilated pupils. It was as if a bucket of iced water had fallen on my head: the fury I had felt a moment before dissipated into the night, creeping back to wherever it had been hiding.

Never again have I felt such a pure, deep desire to hurt someone, and I am pleased that my life has provided me with no further occasions to plunge into such a dark recess of my soul. But that primordial, animalistic feeling left an indelible mark on me, as well as giving me a glimpse into my grandpa’s soul. If a car accident was able to awaken it so easily, I don’t even dare to imagine what deep wounds the infinitely more dramatic experience of combat and war can inflict on the human psyche.

In the end, everyone involved in the accident survived. It took some time for the broken bones to heal and for the wounds to be stitched. My grandma came close to losing an eye, as she had been struck by the gear stick as she was thrown towards the dashboard, but the doctors performed a miracle and it was saved.

When we arrived at the hospital, in an ambulance with screaming sirens, the first person I went to was my grandpa, who was lying on a stretcher. He had been conscious the entire time, but his eyes seemed blank and I sensed that he wasn’t fully aware of what had happened, nor of how we were. I moved into his field of vision, along with my sister, who had been miraculously unharmed in the accident, and I pointed to her with a smile. “Look, grandpa, we’re fine. Don’t worry”. He turned his gaze on us and when he managed to focus he started crying and seemed unable to stop. “Oh thank the Lord, thank you! I would have died if not, I would have died…” he muttered, in tears, his chest shaking from his injuries and his sobs. I said goodbye with a touch and left him in the care of the doctors.

I then went to call my father before anyone else could, to ask him to pick me and my sister up from hospital. I knew that my voice would calm him down. I asked a nurse to lift the receiver and dial the number, as I couldn’t do it alone. When I finally got home, well into the night, I stayed up telling him how the accident had happened, again and again, reliving it obsessively and in great detail.

In the weeks that followed I went back to the hospital many times to visit my grandparents and my mum, all suffering from a variety of broken bones, until they all returned home. One evening I was in my grandpa’s hospital room: we were chatting while he was waiting to be served dinner. “Grandpa, you survived years of war without a scratch, and look what a car accident did in a second” I said at one point. “I thought the same thing, you know?” he smiled at me. “Luckily everyone’s fine”. He stretched out his arm with some difficulty and I took a step towards him. When he hugged me, his embrace took the wind out of me. In the hands that sank into my back, I felt his relief at a nightmare coming to an end.

Counterattack on Monte Marrone

My grandpa’s brush with death on the Gustav line occurred a few days before Easter, which in 1944 fell on the 9th April. General Utili decided, in spite of the danger, to spend that afternoon with the Piedmont Alpine troops in their defensive positions on Monte Marrone. The soldiers had created them by digging holes in the snow, sawing trees, unrolling barbed wire, mining the area in front of them and piling up rocks. But it was a thin, fragile line, with a steep drop behind them that precluded any option of retreat. Halfway between the north and south peaks of the mountain, the artillery that the Alpine troops had dismantled and carried up in pieces was set up. Utili ate a frugal meal with his men and then advised them to be more vigilant than usual that night: the Germans may have tried to take advantage of Easter celebrations to launch their first real counterattack.

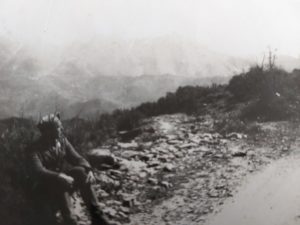

The Alpine troops listened to him, to a degree. That evening they drank probably more than usual, and when dusk fell they joined voices and their songs resounded through the night’s sky. From his position on the slopes of the mountain, my grandpa sat still and listened, a cigarette hanging from his lips. In that lunar landscape, disfigured by war, a choir of hundreds of men’s voices filled the air, rolling between the peaks, showering the trees and filling the valleys. It was a song of liberation: it felt like a slap in the face to death and a gauntlet laid down to the enemy.

One that, as Utili had feared, they picked up. After some time, the Alpine choirs quietened, and the mountains were plunged back into stillness. No one could sleep, however- the German counterattack was in the air and the Alpine troops, Bersaglieri and artillerymen were in a state of high alert, eyes wide open, scanning the darkness.

Towards 3 AM, the Alpine troops positioned on Monte Marrone began to hear suspicious sounds coming from the woods in front of them. To begin with it was just a few rustles, a couple of broken twigs. Moving as slowly as possible, the Piedmont troops began to slide the first shots into the barrels of their weapons, ready to fire. Through the holes they had dug in the snow, the only things visible were their eyes and the muzzles of their guns.

Suddenly, a silent stillness fell across the mountain, and for a moment it seemed that the rocks themselves were holding their breath. The Alpine troops had barely had time to exchange nervous glances from beneath their helmets when a German soldier stepped on a mine hidden among the trees and detonated it. The explosion ended the fragile equilibrium of that wait, and the entire mountain was alive with the furious gunfire of the two sides.

Shooting in the dark, the Germans started to run towards the Italian troops, while the Alpine troops struggled to take aim at the darker outlines running towards them through the woods. Downhill, Italian and Polish artillery activated and began to fire at established targets north of Monte Marrone, to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the mountain peak and to cut off any chance of retreat for those soldiers that had already launched the attack.

My grandpa and the entire Italian formation watched, powerless, their hearts in their throats, as the summit of Monte Marrone was lit up with explosions, while the night sky was sliced by the curved trajectory of tracer bullets, like a macabre firework show.

The conflict was concentrated on the higher of the mountain’s peaks, at the north end of the ridge, and quickly became a hand-to-hand conflict. The German soldiers reached the Italian line and threw themselves across it, turning the initial shooting into a confused, desperate fracas.

The outcome of that altercation hung in the balance for some time, but the Alpine troops eventually prevailed. The last crackles of automatic weapon fire were extinguished at dawn, when the Germans abandoned their attempt to recapture Monte Marrone. The sun rose on a frontline marked by the signs of battle and covered with blood stained snow. During battle the Alpine contingent had lost 25 men, between the dead and injured. It could have been much worse.

While the soldiers worked to rebuild their defences, they ran into an injured German soldier who had been abandoned on the battlefield by his comrades, who either couldn’t find him or couldn’t manage to rescue him. The Italians approached him, tied him to a stretcher and took him down from the mountain, lowering him down the ravine they had climbed during their initial conquest of the mountain. The German reached the destination terrified, sure that it had all been an elaborate plan to scare him and then kill him by dropping him into the void. When he found himself entrusted to the care of Italian doctors, he immediately put his hand to his wallet to offer money to his rescuers. The Alpine troops who had transported him down the mountain started laughing and left him, perplexed and speechless, in the company of a bottle of wine. The war was over, for him.

I remember my grandpa telling me the story of this battle with great admiration. “Those Alpine troops would rather die than retreat by a single metre” he told me, his eyes shimmering.

My grandma was of a different view. “Does that seem like something to be proud of? Everyone dying at war. What then? Well you’re dead! What kind of logic is that?” she commented on one occasion. She wasn’t entirely wrong, and my grandpa didn’t push the matter.

Minefield

The day after the battle, on the 10th April, was Easter Monday. It should have been a day for celebration: the Germans had been held off, and for the moment at least the Italian frontline was not threatened. However, that same night my grandpa was back on patrol. With him was a squad of Bersaglieri and, as always, Borghi. He had not left his side since the start of the war.

They had pushed ahead into a new section between Monte Marrone and Monte Mare, to make sure that the Germans were not planning any further sudden attacks that could catch them unawares. The area, like the rest of the Gustav line, was a snarl of minefields that the Italian contingent had partly cleared, with great patience, during the first weeks on the front. In Italy alone, the Germans had placed over 23.000 anti-personnel mines, which the Allies had nicknamed ‘Bouncing Betties’ after the 1930s American Betty Boop cartoons. Moving around that area was therefore highly risky, even when sheltered from enemy fire. The simple act of placing one foot in front of another was a nerve-wracking endeavour, often seeming to the soldiers like the bravest thing they had done in their lives.

My grandpa and his men were moving silently through the woods. Everything seemed calm, when my grandpa felt a sort of foreboding. He turned back and noticed that his soldiers’ formation had stretched out. With an unexpected sense of concern he turned to Borghi. “Don’t get too far away” he said, trying not to raise his voice.

Borghi looked at him and barely had time to smile back: with his next step, he felt that he had set off the fuze mechanism that would detonate a mine. He took a quick step to the side, holding his breath, while the horror of what would happen made him drop his gun. Indeed, as soon as he moved his foot away, the device jumped a metre into the air and exploded at groin height, shooting its 360 ball bearings out in all directions.

The explosion cut down branches and tree trunks dozens of metres around, somehow missing all the other members of my grandpa’s squad, who were far enough away or had managed to throw themselves to the ground. Borghi, however, was thrown a few metres away, a weak growl issuing from his lips.

My grandpa felt his breath leave him and his heart stop beating. He fell to the ground, stood up again, ran over to Borghi, took off his gun, cradled his head in his hands and screamed at him to talk, while with one hand he tried in vain to close the gaping wound that had opened on his body. It was clear that there was nothing to be done: Borghi’s lower half had disappeared. My grandpa held him and stroked him, forcing himself to look him in the eyes and ignore his torment. A few moments later, Borghi’s eyes filled with tears, the hand that had been gripping my grandpa’s arm fell weak and his body, which had been spasming, suddenly relaxed. He was twenty-three years old.

My grandpa did not move. He stayed kneeling, rocking back and forth, Borghi’s head in his hands, fighting the pained groans escaping his throat. He tried closing his eyes to shut out the world, but it was pointless – his friend’s body was still there, with the indifferent texture of the dead, unable to say even a last goodbye.

The other Bersaglieri approached in silence and stood behind him. Someone placed a hand on his shoulder and slowly helped him up. My grandpa grasped his gun, turned towards base camp and started walking without looking around, as lonely as the last man alive. Conquering fear, clutching at life had been difficult until then. From that moment on, without his dearest friend, it would be a dance with madness.

When I was a boy, although he never went into detail, my grandpa often spoke to me about his orderly, the circumstances of his death and the closeness of their friendship. But I could not understand his loss, and even now I can only begin to try to understand it. Even though I spent many years with him, I never gave him a consoling hug.

Recognition

The conquest and defence of Monte Marrone was widely reported on in the media. On the 1st April, BBC Radio celebrated it, without specifying that it had been carried out by Italian soldiers: “In the central section of the battle line, allied troops advanced by around two kilometres, conquering Monte Marrone (…), whose peak, twenty-one kilometres north east of Cassino, overlooks a German supply route”.

On the 11th April, however, it reported on the repelled German counterattack, this time mentioning the Italians: “Italian troops in the main section of the 5th Army repelled German counterattacks, inflicting losses on the enemy”.

The allied officers with whom the Italians had contact also congratulated the Grouping. General Sulik, the commander of the Kersowa Division, expressed it like this: “The action on Monte Marrone (…) is the best demonstration of the excellent preparatory work carried out by the chief of staff, and the decisive rebuffing of the enemy, as well as the continued patrol work, an expression of the high combat quality of the soldiers of the 1st Italian Motorised Grouping”.

General Alexander, commander of allied forces in Italy, wrote the following: “Throughout the winter you have fought valiantly (…). I, and those who know of this, are fully aware of how magnificently you have fought, against almost insuperable obstacles, in a war on steep and rocky snow-covered mountains, and in valleys broken up by rivers and mud, against a tenacious enemy. You have won the world’s admiration (…). Allied forces are currently gathering (…) to annihilate the enemy once and for all. In Italy we were given the honour of firing the first shot”.

In 1975, a cross with an eagle taking flight was placed on the highest peak of Monte Marrone by the National Alpine Association in commemoration of the battle. The monument still stands there, watching over the summit.

With the conquest of Monte Marrone, the frontline controlled by the Italians extended to the right, to beyond the source of the Volturno, as far as Monte Curvale and Monte Santa Croce, which overlook the villages of Foci, San Vittorino and Cerretta. The repositioning was done in such a way that it allowed various allied units to move to other areas of the front and enjoy a brief rest period in the rear, ahead of operation Diadem, the final assault on the Gustav line.

On the 15th April, during this reorganisation, the Grouping went from being under the orders of the Polish to coming under the 10th British Army Corps. The Polish General Anders wrote to Utili to bid him farewell: “I must express my most sincere satisfaction in having known and collaborated with you, your chief of staff and the troops of the 1st Motorised Grouping, and I heartily appreciate the sincere relations that we have enjoyed as a result”.

On the 18th March, the Motorised Group changed name, becoming the Italian Liberation Corps (CIL in its Italian acronym). It was a sort of official recognition of their contribution to the war effort fighting alongside the Allies. By that date, the Italian contingent had recorded 93 deaths, 315 injured and 175 missing in action. A total of 583 losses, 340 of which had occurred during the battle of Monte Lungo in December 1943 and 243 on the Gustav Line. One of those was Borghi.

While the Allies were preparing for their final push against the German defences, on the 22nd April the first national unity government was formed, with Badoglio continuing in his role as Prime Minister. This became possible after the Communist Party of Italy, led by Palmiro Togliatti, agreed to join the government alongside the other parties, thereby sending a clear signal that they were prioritising the antifascist fight over deposing the monarchy. As a result of this shift, all the antifascist parties, i.e. the Christian Democrats, the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, the Liberal Party, the Democratic Labour Party and the Action Party were for the first time grouped together in an executive body. It was an important step forward in achieving unity in the fight against Nazi-Fascist forces, although the government would not survive long beyond the liberation of Rome.

Monte Mare

At the beginning of May, the sun finally began to warm the mountains, the air smelled like springtime and operation Diadem was almost ready to launch.

The Piedmont Alpine Battalion was then withdrawn from the frontline for a short rest period, and replaced on Monte Marrone by the Bersaglieri of the XXXIII and XXIX Battalions. My grandpa climbed it while still enclosed in a tomb of silent isolation after Borghi’s death.

On the 11th May, the day before the big allied offensive, the Germans once again attempted to take Monte Marrone. By this point, however, the Bersaglieri had occupied it in great numbers and they repelled the attack. My grandpa opened fire with a new fury that day, and this time, unlike in Corsica, he aimed straight with every shot. Amid the din of each gunshot he sought revenge, hunting it down until the last German soldier fell or fled. But when the day came to an end, he had still found no peace. He felt sorry for himself and felt like the earth he walked on was sucking him down into a deep chasm. That evening he went to find a spot far from his men, curled up among the rocks and closed his eyes. Any company felt like an unbearable burden.

The same day, a handful of Italian soldiers managed for the first time to reach Monte Mare, the capture of which would preclude access to Montecassino from the Mainarde mountains, which mark the border between the Lazio and Molise regions. The attack was the result of a rather uncoordinated, unplanned advance, involving only the “Arditi” platoons of the Bersaglieri. This group of soldiers had managed to occupy it and hold it from 10 in the morning until 9 at night, when they were overwhelmed by the inevitable counterattack, which was launched at around 4 in the afternoon. The German reaction was indeed impossible to contain, in part thanks to the Italian artillery’s poor preparation, as they had had neither the time nor the means to prepare cover fire before combat began.

During these battles, Alpine Lieutenant Enrico Guerriera, who had remained on duty at the artillery installed on Monte Marrone, realised that the bersaglieri positioned on Monte Mare were facing greater difficulty than those fighting alongside my grandpa. Disobeying orders, he left his position to go to provide them with backup, and managed to join the fighting. Enduring repeated head, back and arm injuries, he refused to seek shelter and was eventually mown down by machine gun fire to the chest. For his courage, he was awarded a gold medal for military valour with the following comments: “In a moment when parts of his own section were not immediately involved in the action, and given that a unit of Arditi Bersaglieri were under heavy fire in a difficult sector, he ran to assist (…) Having contributed with great efficacy (…) to neutralising repeated German assaults, he left the communication trench in an attempt to take out an enemy automatic weapon position with a hand grenade. In that bold attempt he was injured. In spite of that he persisted in his action, and though he was injured twice more, he continued to drag himself towards the enemy, until he was mortally wounded”.

Guerriera’s son had given him a rubber teddy bear as a good luck charm and souvenir when he left to go to war. Guerriera kept it with him at all times: he said that with that talisman, nothing would happen to him. During the fighting of the 11th May, however, he had left it in his tent. The toy is now on display at the Monte Lungo military museum.

At the end of the day, the Italians were forced to retreat from Monte Mare, having suffered 9 injuries, 2 soldiers missing and 3 dead, including Guerriera. The CIL men were not lacking in enthusiasm. Discipline and organisation left something to be desired, however. In any case, the fighting that day prevented Kesselring from moving his men from the Mainarde mountains to the Cassino section, precisely as the allied offensive was being launched.

The final assault on the Gustav line

Operation Diadem got underway at 11pm on the 11th May. After lengthy preparations, more than 2000 artillery weapons began firing along the length of the line, which became a firestorm. This time, the offensive was broad-based and would force the Germans to fight along a line several kilometres long, rather than attempting to breach it at a single point, as had been done in previous battles. While the artillery was doing its job, allied aviation began a series of bomb attacks on the German rear, hitting road and rail targets before focusing on the more strictly military targets of the Gustav line.

Once the attack had begun, Churchill wrote to General Alexander: “All our thoughts and hopes are with you, in what I believe and hope will be the decisive battle, fought to the utmost”. After months of stalemate, the entire allied command was watching the battle with barely concealed apprehension.

Once the bombing had been completed, the 8th British Army sent 300,000 British, Canadian, New Zealand, Indian and Polish soldiers to attack the line in the Liri Valley, Cassino and Montecassino. The 5th American Army hurled 170,000 American and French troops into a small section 32 kilometres wide south of Cassino, focusing on the Tyrrhenian coast and the Aurunci mountains.

The battles raged for a long time, but in spite of the violent push, the Germans endured, especially in the first three days.

The CIL did not advance, but stayed guarding its positions in the Mainarde mountains, once again repelling the latest German counterattack on Monte Marrone on the 13th May, which was launched at 10:30pm. The Italian artillery positioned on the ridge fired on the advancing Germans at point blank range, immediately followed by the other Italian cannons positioned downhill and the light weapons of the troops in the trenches of the frontline. Once again, the enemy’s advance was hindered, and the Germans had to beat a retreat.

Those days seemed endless to my grandpa. It must have seemed like hell was swallowing up the whole world. Battles raged along the entire frontline, aerial and artillery bombings were incessant, and he and his men had already had to ward off two counterattacks in three days.

I remember him telling me that he hadn’t managed to sleep for several nights in a row. The sight that he beheld was of a destruction so pure, so perfect, that the flash of flames hurt his eyes and the roar of explosions ripped through his ears. The only feelings that the men fighting in those battles harboured in their hearts was crazed fury and a ruthless desire to stay alive.

On the 14th May the German line began to crumble. The French breached the section in the Aurunci mountains, and the 71st German division blocking their route began to buckle. The left flank of the allied formation began to advance, while at the same time, Canadian tanks finally made it across the Rapido river, which at the time passed through the centre of Cassino (today it runs to the south). Once they had made it to the other shore, they managed to provide the armoured support the allied troops had been lacking during the first three battles, that would quash any German counterattack.

At that point, Kesselring understood that he had lost the match. If his right flank along the Tyrrhenian sea folded completely, there was a real risk that the Allies would flood in and take his men trapped in Cassino from the rear, as well as his positions at the centre of the formation. He had no other choice but to retreat.

The final withdrawal occurred during the night of the 17th and the 18th May. On the morning of the 18th, soldiers from the Polish contingent managed to occupy the ruins of Montecassino Abbey, which had just been abandoned by German paratroopers, eventually succeeding in hoisting their flags. Their latest assault came at the cost of almost 4,000 men, between the dead, injured and missing. But the Gustav line had been broken.

Immediately after this breakthrough, the section of the frontline that came under the responsibility of the CIL was extended to the left, up to national road 627, which connects Isernia to Sora, via Atina, to the west of Monte Marrone. But with the Germans on the move, Italians would also soon be called up to mobilise and pursue them, to keep them moving in retreat and fully exploit the allied advantage.

In the meantime, the Americans stuck in Anzio had been reinforced by the 36th Texas Division, the same that had fought in Monte Lungo alongside the Italians in December 1943. With the arrival of that unit and the Germans on the back foot, General Truscott’s men finally attacked on the 23rd May, to break through the siege in which they had been trapped for four months. General Alexander’s plan was that the contingent that had landed in Anzio should head for Valmontone and occupy the Casilina road, to cut off the Germans fleeing the Gustav line in retreat. It was a unique opportunity to surround and destroy a considerable portion of the German forces in Italy, which would bring fighting to a quicker end.

But General Clark’s ambition won the toss. He was obsessed with the idea of going down in history as the man who liberated Rome and wanted to hasten this victory so as to get ahead of the Normandy landings, which he knew were ready to launch. This forced Truscott to change his order to advance, focusing instead on the Italian capital.

When he realised this, Churchill was vehemently opposed, but there was nothing to be done: Alexander could not change his mind. The Germans were thus able to get away using mountain paths inland, in an orderly retreat that allowed them to reposition further to the north, where they held the Allies to several more long months of battles.

Advancing on Rome, the Allies found it empty and intact, abandoned but without destruction by the escaping German contingent, and they entered it on the 4th June without firing a shot. In the end, its status as an open city had been sanctioned by the enemy, too.

Clark got his victory and would remain convinced that it was the right thing to do. Speaking about his decision to head straight for Rome, he said “We did not just want the honour of conquering Rome… we felt that we had amply earned it (…). We wanted people back home to know that it had been the 5th Army that had got the job done, and at what price”. On the 5th June a victorious Clark reached the Campidoglio in Rome in his jeep. But the very next day, Operation Overlord, in other words the Normandy landings, stole his thunder, pushing the events in Italy into the background, even though Cassino had made the invasion of France easier by diverting Hitler’s troops. The glory that Clark had dreamed of, and which prolonged the war in Italy, was only celebrated in the press and news reels for 24 hours.

Operation Chianti

The men of the CIL had been thrown forward to the front on the 27th May, under Operation Chianti, agreed on with the 8th British Army, to pursue the retreating Germans across the Mainarde mountains and enable the Allies to advance safely to Atina, following state road 627, which snaked along the valley floor. The attack began at 7 AM, after artillery shelling, and involved all forces available to Utili. My grandpa and the bersaglieri were not engaged in combat during this operation, but they followed the Italian contingent for three consecutive days of marching through the mountains, ready to enter the fray if needed.

On the first day of the advance, Alpine troops had occupied Monte Mare by the morning, which had been abandoned by the Germans and fell permanently into Italian hands after the battles over it on the 11th May.

The 184th Paratrooper Regiment, fresh from Sardinia, instead attacked Monte Cavallo, the highest of the Mainarde mountains at 2039m, which was still being defended by some German units. Theirs was by now a rear-guard action, however: Kesselring’s men were simply trying to slow down the Allies’ advance, not to stop them. Enemy fire forced the paratroopers to advance with caution, approaching from the north and south, as the east face of the mountain presented only inaccessible rocky bastions. They reached their target at 11am on the 28th May.

After this last-ditch attempt at resistance, the Germans simply gave up trying to prevent Utili’s men from advancing, and abandoned the field. The 184th Paratrooper Regiment therefore took San Biagio Saracinisco, on the far left of the Italian formation and on the way to Atina, while the 68th infantry regiment reached Monte Mattone, immediately to the north of Lake Barrea, marking the eastern limit of the CIL offensive. On the 29th May, CIL units finally descended into the village of Picinisco, east of Atina, from their positions on Balzo della Cicogna, ensuring the Allies safe passage along state road 627.

This latter action finally brought an end to the CIL’s operational tour on the Gustav line and the Mainarde mountains. I remember that my grandpa told me several times about being completely exhausted at the end of that period, unable to recognise himself or think lucid thoughts. He spent the next three days sleeping almost constantly, to the extent that the medical staff began to worry about him. His body just needed time to recover and to ignore all demands on it for a while.

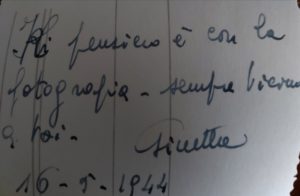

When he recovered some strength, he was finally able to read the post he had received from Ginetta, which had been unable to be delivered during the heaviest fighting. Among her letters there was also a photo of her smiling, on the back of which she wrote that she was thinking of him and was close to him. When he saw it, his homesickness and desire to see her swelled like a wave bursting through a dam. But having lived through such an ordeal, he feared that he had been flung deep into a place where Ginetta could never reach him. He placed the photo in his wallet, and as he did, he saw the blood and mud encrusted on his hands and wondered whether he would have to hide them for the rest of his life.

From the 1st of June and for the three days after, the men of the CIL were loaded into trucks and taken to the Adriatic coast, with orders to advance northwards in the coming weeks. This transfer, from the 10th to the 5th British Army Corps, lost them any possibility of parading through Rome in victory. In spite of the heavy toll in lives, the Allies would not grant them that privilege.

General McCreery, commander of the 10th British Corps, wrote to Utili to bid him farewell: “Dear General Utili, I am sorry not to have seen you today. I wish to thank you, Colonel Lombardi and all members of the CIL for the enthusiastic and effective cooperation you have shown my forces. I would like to congratulate the military at every grade for their recent operations (…). The operation was carried out speedily and your troops showed determination in facing the enemy and a strong spirit of resistance (…). I wish all members of the CIL the best of luck and success in future operations. I am truly sorry to see you leave the 10th Corps”. A letter that rings true: the CIL genuinely had earned the Allies’ respect in the field.

General Leese, commander of the 8th British Army, wrote to Utili around the same time: “My dear General Utili, I must congratulate you and your troops for the admirable progress made in your recent battles. Your success in driving the enemy out of significant mountainous areas (…) has been of great assistance to our advance (…). I am extremely grateful to you and all the troops you command, and am sure that your successes, which were a first for the 8th Army, augur more victories in the near future”.

‘Marocchinate’ – The Moroccan incidents

The last few days of May 1944 should have been a happy time for Italy, with the demolition of the Gustav line and the liberation of Rome. Instead, for many inhabitants of villages in Lazio, it was just the beginning of a new, unexpected nightmare that continued into Tuscany and the island of Elba. A nightmare that I hope never affected my grandma, who had stayed in Altopascio, in the province of Lucca, for the duration of the war.

After the frontline was broken, the French colonial troops gave free rein to the systematic rape of any women that had the misfortune to come across them. It is of course possible that other allied soldiers occasionally joined the horror, but it appears established that the goumiers were responsible in the majority of cases. What remains to be clarified is the original motivation for their behaviour.

According to a frequently cited reconstruction of the facts, at dawn at the last battle of Cassino, the commander of the French contingent, General Juin, supposedly circulated to the goumiers a leaflet in French and Arabic, containing the following instructions: “Soldiers! This time I am not only offering you the liberation of your lands if you win this battle. Behind enemy lines there are women, homes, there is some of the best wine in the world, there is gold. All that will be yours if you win (…). For fifty hours you will be the undisputed masters of everything that lies beyond enemy lines. No one will punish you for whatever you do, no one will hold you accountable for what you take”.

The original of this pamphlet has never been found, however, and it is unusual that Juin should put into writing instructions that incited his troops to commit crimes.

Even if the leaflet theory were to be proven false, the acquiescence of allied command and the methodical nature of the violence committed seems to suggest a context in which the Moroccan and Algerian contingents were allowed, more or less tacitly, a certain freedom of action with regards to the civilian population as payment for their engagement in battle. The goumiers would, in other words, be given a so-called ‘prize’.

No one knows for sure how many episodes of violence took place – many were not reported, out of shame or because the reports were lost in the chaos of war. Others were buried to avoid damaging the reputation of the Allies as liberators of Italy, or so as not to compromise peacetime relations between France and Italy. There is no doubt that these rapes affected several thousand women, with current estimates varying between 12,000 and 30,000 victims. On several occasions, allied soldiers from other contingents intervened to stop the goumiers, but command never encouraged that action. Indeed, they wished to reduce the possibility of allied soldiers firing on each other rather than the Germans. The solution came only in October 1944, when the colonial troops were transferred to Provence to contribute to the liberation of France.

The worst affected areas were the provinces of Frosinone and Latina. Allied police forces, who had noticed these incidents, noted that “in many cases, Moroccan troops had forced the young women’s parents or married women’s husbands to be present” at the violence. To avoid this punishment, many women feigned illness, covered themselves in mud to make themselves as unattractive as possible, or offered themselves as victims so that their daughters may avoid the same fate. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not.

Among the various witness testimonies gathered, one particularly heart-breaking one was given by an inhabitant of Itri, recounting what had happened to his family: “A group of Moroccans came to the house, took my 20-year-old sister-in-law (…) to a haybarn, where she was raped by four of them (…) one of my nieces, a 23-year-old woman, was taken to the countryside and raped by seven Moroccans (…). Another of my nieces, a 24-year-old woman, was trying to escape with her goats when she was raped by a group of Moroccans. They came to the house, (…) everyone resisted them but were beaten (…). They took away all my livestock (…). That same evening, other Moroccans came to the house where I was with my wife and my sister-in-law, they raided it and then took away my sister-in-law, who is 52 years old, and used violence on her”.

The problem took on such proportions that at one point the Italian authorities made an official complaint. General Messe, the chief of staff of the cobelligerent Italian army, actually wrote to British General Noel Mason MacFarlane, the head of the Allied Military Control Commission, who was in charge of enforcing the armistice between Italy and the Allies, to complain of “profoundly inhumane” incidents that instilled “a feeling of profound shock and hostility in the local population towards Moroccan troops”. But the note had no significant effect.

On the one hand, the Allies did not wish to intervene decisively to stop the goumiers, on the other hand they turned a blind eye when the civilian population took justice into their own hands. In Sicily, for example, where the problem had already been seen on a reduced scale after the allied landings of July 1943, several goumiers who had been accused of rape were found dead, their genitals cut off. Others had been killed with farm tools, castrated, ripped to shreds and fed to swine. Local revenge was ruthless, and the Allies allowed those events to run their course.

By the end of the war, however, many women died as a result of the violence they had suffered. Of the survivors, few received a war pension after hostilities ceased. The Italian state in fact reserved compensation for those women who had contracted a venereal disease and were able to demonstrate that they had been subjected to force. Others were ignored and sacrificed to the logic of a politics and a world that seemed to be doing everything possible to ignore their suffering.

The goumiers’ violence, which became known by the euphemism ‘le marocchinate’, or ‘the Moroccan incidents’, was recounted in Alberto Moravia’s 1957 book Two Women, which was adapted for the big screen in Vittorio de Sica’s eponymous film in 1960. Those two works of art brought the trauma of those months into the Italian collective memory.

Resistance to the end

The battles of Cassino and Anzio, as well as having repercussions on the civilian population, were an orgy of violence such that Italy had never seen. It has been estimated that frontline battles incurred 100,000 losses to allied forces and 60,000 to the Germans, between dead, injured and missing men.

After that bloodbath and the Normandy landings, as it became increasingly clear that Germany would lose the war, General von Senger und Etterlin, who had led the German troops in Corsica before being transferred to Italy, commented, disheartened: “I wonder what verdict history will reserve for those of us intelligent enough to know that defeat is inevitable and still continue to fight and contribute to the bloodshed”.

My grandpa witnessed first-hand this useless, fanatical resistance over the course of the following months, as he advanced up the Adriatic coast through Abruzzo and Marche.

Thanks for another truly compelling read, Filippo!

I am a huge fan of how you combine the grand perspective with the individual one. It’s like in my favourite history books. Except here, the individual perspective is truly personal. And it really shines through. I really like how the narrative of your grandfather’s experiences does not feel “exaggerated”; for instance by also mentioning the time away from the front and the special emotions of transitioning to and from the frontlines.

I also found your juxtapositions of the military with civilian experiences to be very good inclusions. Not least your own brush with death (that one shocked me!) but also the atrocities committed by some Allied troops during/after the liberation. Unfortunately a part of the history that cannot and should not be ignored (but for instance, I did not know this about the French colonial troops in Italy).

Thank you very much Stan! Really glad to hear that 🙂

It certainly is a lot of fun and very interesting for me to research these events and write about them. And it’s a rather emotional process too, considering I’m talking about my grandpa.

I have been researching the battles around the Montecassino area for the past few days, and your writing has given me a real feel for what happened and the issues that the Allies encountered in that area. Ihave a very real connection to the area as my mother was born and raised in Vallerotonda which is a village not that far from the Gustav line. The atrocities of war are harrowing but what happened to many Italian women, men and even children the day after the last battle by French goumiers has left me feeling upset beyond belief and I just hope that nobody in my family was affected.

Dear Lynda, thank you very much for leaving this comment. I’m glad that what you read on this blog helped you to get a better understanding of the battle around Montecassino. And I also sincerely hope that your family was not affected by it or but what happened in its aftermath.. Wishing you all the best and thanks again for visiting the blog, Filippo